Σπήλαιο της Αντιπάρου

Cave of Antiparos - Andiparos - Cave of Agios Ioánnis - Agia Paraskeví

Useful Information

| Location: |

Αντίπαρος, Κυκλάδες 840 07.

13 km south of Antiparos village, almost at the top of a more than 200 m high mountain. Regular bus from the harbour in Antiparos once an hour. (36.990561, 25.059372) |

| Open: |

APR to OCT daily 10-16. [2021] |

| Fee: |

Adults EUR 6, Children (6-12) EUR 3, Children (0-5) free. Ticket includes visit to Historical and Folklore Museum of Antiparos. [2021] |

| Classification: |

Karst Cave Karst Cave

|

| Light: |

LED LED

|

| Dimension: |

L=89 m, VR=85 m, W=60 m, A=171 m asl, T=15 °C, H=65%. Portal: W=20 m, H=10 m. |

| Guided tours: |

L=200 m, VR=70 m, St=411.

Audioguide

Leaflets

Leaflets

|

| Photography: | allowed, no flash |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: |

Trevor Shaw (1992):

History of Cave Science,

pp 14, 142, 178, 180-182, 241, 244, 255, 275, 277

G. Bakalakis (1969): Aus den Grotten in Antiparos und Paros. Archäologischer Anzeiger, p. 125-132. De Gruyter | 1969. doi online

Otto F. A. Meinardus (1980): Die Höhle von Antiparos aus der Sicht der Reisenden des 17. bis 19. Jahrhunderts, Die Höhle, Zeitschrift für Karst- und Höhlenkunde, Heft 1, 31. Jahrgang, April 1980, ISSN 0018-3091. pdf

M. H . Omont (1892): Relation de la visite du Marquis de Nointel ä la Grotte d’Antiparos Bulletin de geographie historique et descriptive, 4, 1892, 1—33.

Albert Vandal (1900): L’Odyssée d’Un Ambassadeur: Les Voyages Du Marquis de Nointel (1670-1680), Paris 1900.

Stephan Kempe, Christhild Ketz-Kempe, Erika Kempe (2009): Early cave visits by women and the travel accounts of Lady Elisabeth Craven to the Grotto of Antiparos (1786) and Johanna Schopenhauer to Peaks Cavern (1803), Conference: 15th International Congress of SpeleologyAt: Kerrville, Texas, USA, July 19-26,2009, Volume: Proceedings: 1993-1999. researchgate |

| Address: |

Cave of Antiparos, Tel: +30-248-61315.

Town Council, Tel: +30-2840-6121. KEDA, Tel: +30-22840-61640. E-mail: |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 7th century BC | visited by the poet Archilochus of Paros (680–645 BC). |

| 5th century BC | hideout for Macedonian generals. |

| 15th century | cave explored. |

| 1673 | Christmas mass held in the cave, for Charles François Ollier, marquis de Nointel, French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and numerous companions. |

| 1700 | visited by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort. |

| 1714 | a small chapel of St. John the Theologian is built at the cave entrance, consecrated by Metropolitan Neophytos Mavromatis of Naupaktos and Artis. |

| 1738 | The Count of Sandwich visits the cave with thirty companions and admires the beauty of the natural formations. |

| 1767 | visit by Baron Friedrich von Riedesel, the priest at the church guides him. |

| 1770-1774 | many stalactites cut off during the Russian occupation by crews of Russian ships in the harbour. |

| 1776 | visited by Marie-Gabriel-Florent-Auguste Comte de Choiseul-Gouffier (*1752-✝1817). |

| MAY-1786 | Elizabeth Craven (*1750-✝1828) first known woman who visited the cave. |

| 1802 | visit by the famous English mineralogist Edward David Clarke. |

| 1806 | report of the English scholar and topographer William Martin Leake. |

| 27-SEP-1840 | visited by Otto, King of Greece. |

| 1876 | visited by King Otto and Queen Olga. |

| 1879 | visited by priest and traveller Henry Fanshawe Tozer. |

| 1880 | visited by J. Theodore Bent. |

| 1960s | first development as a show cave with stairs and ladders. |

| 1995 | electric light and new railings of stainless steel. |

| 1996 | new road to the cave completed. |

| 2009 | cave and surroundings of the cave entrance modernized, LED light system installed. |

Description

On the small island of Antiparos, southwest of Paros, an enormous cave descends 70 m into the earth. Even in August travellers will feel damp and chilly as they descend the 400 cement steps into the cave. Famous visitors have carved their names on the walls, including Lord Byron and King Otto, the King of Greece in 1840.

On three occasions the French Ambassador at Constantinople, the Marquis de Nointel, Charles François Ollier, celebrated midnight mass here, using an enormous truncated stalagmite as an altar. At its base is this inscription: celebrated midnight mass here, using an enormous truncated stalagmite as an altar.

HIC IPSE CHRISTUS / EJUS NATALIE DIE MEDIA CELEBRATO / MDCLXXIII

(Here midnight mass was celebrated on Christmas 1673)

Islanders claim that older inscriptions have been destroyed by overwriting by runaways, who had been wrongfully accused of attempting to assassinate Alexander the Great and were hiding in fear of retribution.

Another famous visitor was Joseph Pitton de Tourenefort, Professor of Botany at the Jardin du Roi in France. He visited the cave in August 1700 and described the speleothems as growing like plants or vegetation.

Boats from Paros take passengers directly to the landing stage on the shore below the cave and drivers wait there with donkeys for those who want a ride up the hill of St John to the cave’s entrance. Or go to Pounda and take the car ferry across, a 5-minute ride.

Text by Tony Oldham (2002). With kind permission.

The Σπήλαιο της Αντιπάρου (Cave of Antiparos) is named after the island. It was known since the Neolithic, and it was visited during the Bronze Age, the Classical Greek Antiquity, which is proven by archaeological findings. It was used as a place of worship for the goddess Artemis. The locals tell about inscriptions of visits during antiquity, for example by the poet Archilochus of Paros. However, the scholars are actually unable to even tell when he lived, some say 728–650 BC, Felix Jacoby dated him 680–645 BC, Robin Lane Fox dated him 740–680 BC. Details about his life are forgotten, if they are not written in the fragments of his poems which survived. Our knowledge is at least fragmentary. And the legendary inscription in the cave is long destroyed, if it ever existed.

The next legend is about Macedonian generals, who had been attempting a failed assassination of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC), and were hiding in the cave in fear of retribution. The popular belief is based on an inscription which still exists and says:

EΠΙ ΚΡΙΤΩΝΟΣ ΟΙ∆ΕΗΛΘΟΝ

ΜΕΝΑΝ∆ΡΟΣ ΣΟΜΑΡΧΟΣ ΜΕΝΕΚΡΑΤΗΣ ΑΝΤΙΠΑΡΟΣ ΙΠΠΟΜΕ∆ΩΝ ΑΡΙΣΤΕΑΣ ΦΙΛΕΑΣ ∆ΙΟ-ΓΕΝΟΣ ΦΙΛΟΚΤΡΑΤΟΣ ΟΝΗΣΙΜΟΣ

Epi Kriton Odeylon

Menander Somarchos Menekratis Antiparos Hippomedon Aristeas Phileas Dio-genos Philoctratos Onesimus

During the magistracy of Krito

Menander, Socharmos, Menekrates, Antipatros, Hippomedon, Aristeas, Phileas, Gorgos, Diogenes, Philokrates, Onesimos

came to this place.

Obviously this is just a list of greek names. The legend insists that they were actually generals and tried to assassinate Alexander the Great. You will not read about this assassination attempt in his biography though. And other older inscriptions which may or may not have existed were destroyed during the 19th century. Modern archaeologists were not able to find them.

But while antiquity used caves as temples, later generations feared them. It was believed that the cave was one of the entrances to the underworld, to Hades. With Christianisation hades became hell. For two millennia the cave was most likely not visited, at least there is no evidence of visits. On the other hand the inhabitants of Antiparos called it Katafygi, a name given to caves which were used as a hideout. Before entering the cave, a shot was fired to drive away the ghosts and goblins.

The French Ambassador at Constantinople, the Marquis de Nointel, Charles François Ollier, is generally thought to be the first explorer of the cave. Visits during antiquity are elusive, mostly because there are no remains and no written documentation. The Marquis was different, he produced a written documentation about the account, a rather lengthy story how he heroically conquered the cave. He romanticised the event and called the cave Gold Grotto, based on an obscure pun on the ancient Greek name of the island of Antiparos. The Marquis and his entourage of 500 people actually visited the cave for three days, equipped with ropes and ladders they made the dangerous descent and explored the cave completely. In his entourage were some clergymen, some merchants, but also inhabitants of the island. A hundred large torches made of yellow wax and 400 oil lamps illuminated the interior of the cave day and night.

On Christmas Eve, at midnight, the Marquis had his Capuchin house chaplains celebrate Holy Mass. Servants stationed at certain intervals from the cave entrance to the innermost part of the cave gave signs with their handkerchiefs, so that in the momnet of the holy consecration 24 stone mortars outside the cave fired firecrackers. Trumpets, hautbois, violins and whistles helped to make the process even more solemn. To commemorate the event the enormous truncated stalagmite they used as an altar, was named Αγία Τραπέζα (Holy Table) and an inscription was placed beneath it.

HIC IPSE CHRISTUS

ADFUIT EJUS NATALIE

DIE MEDIA NOCTE

CELEBRATO

MDCLXXIII

Over here Christ himself was present, when his birthday was celebrated at midnight, 1673

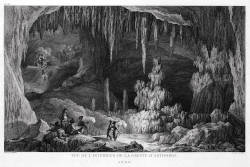

The Marquis spent the three nights in a natural cabinet opposite the altar, 7 to 8 feet long and just as wide. The Capuchin fathers, after a long search, managed to discover a spring that provided sufficient water for the underground inhabitants. The draughtsman and the masons who belonged to the Marquis’ retinue were commissioned to cut down the most beautiful stalagmites and stalactites. Some of these pieces found their way to the Royal Academy of Inscriptions and Coins in Paris. An impression of the event has been preserved in a steel engraving.

Another Latin inscription at the entrance to the cave referred to the same event. It was recorded in 1771 by Heinrich Leonhard Graf Pasch van Krienen, but is no longer legible today. The text read:

HOC ANTRUM EX NATURA MIRACULIS RARISSIMUM UNA CUM COMITATU RECESSIBUS EJUSDEM PROFUNDI ORIBUS ET AB - DITIORIBUS PENETRATIS SUSPICIEBAT ET SATIS SUSPICI NON POSSE EXISTIMABAT CAR. FRAN. OLIER DE NOINTEL IMP. GALLIARUM LEGATUS DIE NAT. CHR. QUO CONSACRATUM FUIT AN. MDCLXXIII

This cave, which is unique among the wonders of nature, was visited by the French Cardinal [or Charles Francois] Oliver of Nointel, ambassador of the French Empire, on the birthday of Christ, on which the cave was consecrated in 1673, together with his companions, after the deeper and more remote parts had been explored, and he believed that it could not be admired enough.

Since this story made the cave well known, it was regularly visited, with increasing numbers of visitors since the 19th century. The number of old engravings, woodcuts and lithographs, which were published, give an idea. The cave was famous all over Europe, at least among educated people, and the only cave known on Antiparos. And it was subject to a multitude of damages. The engravings and graffities for one, the people who took a souvenir by breaking a speleothem. During the Russian occupation of 1770-74, Russian officers cut off many stalactites. Today they can be seen in the Eremitage in St. Petersburg. It was also damaged during German occupation in World War II, German soldiers used it for rifle practice.

In 1700 the cave was visited by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, who was sent to explore the Cyclades by French King Louis XIV. His description shows that he actually hated the visit. He even misunderstood the speleothems with marble, which was criticized by numerous later visitors. For him, the strangest thing on this island was the cave and the underground grotto, note the idiosyncratic distinction.

"The former has an arched vault and is supported by a pillar; several names are engraved in it.

Through it one comes to a rough slope and through a dark hole into the grotto.

You must have torches with you and then climb into a terrible abyss with the help of a rope.

A ladder is also placed at the edge of this abyss, on which one climbs tremblingly over a vertically hewn rock.

From time to time you have to lie backwards on a rock and tie yourself to the rope to avoid falling into the most horrible morasses.

There were still the remains of the ladder that the Marquis of Nointel used for his descent.

But the ladder had become so rotten that our companions had to fetch a new one.

After a thousand dangers we finally reach the cave.

One part is very rough, the other quite flat.

In various places you can see large, rounded lumps or points like Jupiter’s thunderbolts.

Lances of amazing length hang from them.

On the right and on the left you can see cloths or curtains, which form cabinets of their own, as it were.

Below them one notices a large pavilion formed by outgrowths representing the head of a cauliflower.

Then pillars of marble rise, like tree trunks, and everything is crystallised white and transparent.

All these figures have grown out of the marble, as it were, without there being any water in the place; indeed, much is still growing.

To the left in the cave one sees a pyramid called the altar..."

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort

An inscription from 1776 is quite funny, though we do not know much about the story behind.

Hélène Täscher, incomparable femme, trésor du marquis de Chambert, à Paris 1776

Hélène Täscher, unequalled lady, treasure of the marquis of Chambert, Paris 1776

The cave was visited by Otto, King of Greece, and Queen Amalia, in 1840. While he descended into the cave, his wife waited in front of the cave. She lost her bracelet set with diamonds, but two years later it was returned to her by a small trader. The lucky finder received a reward of 10,000 drachmas. In 1876 when King Georg and Queen Olga visited the cave, this Queen was braver and actually visited the cave. It is also quite sympathetic that they refrained from graffiti in the cave.

The cave is located on Ai-Yiannis hill, above Soros, at 171 m asl. The old way to visit the cave was by boat from the harbour of Antiparos, to the beach near Soros, below the cave. The boat ride is really pleasant, but the 1.5 hours, almost 200 m, ascend to the cave in the hot summer sun was pretty tiring. It was made by foot or on a donkey, but we are not convinced the donkey ride was actually less tiring.

The cave of Antiparos is often mentioned as the oldest show cave of the world. This is probably the result of the numerous famous people visiting the cave. Unfortunately those mentions avoid to tell a date or event, which actually was the first show cave visit. The problem is: all those visits were cave exploration tours and not tourist tours, even if they were made by nobility. There was no development of any kind, the visitors had to abseil and reascend various drops, and there was no guide in any way, although the locals were happy to rent their donkeys. Only the Christmas mass in 1673, which was obviously not cave exploration, qualifies at least partly as a touristic visit. But at some point in the 20th century there were at least some trails and ladders, but still no official operator and not light.

After many centuries of low-key development, the cave was finally developed in the mid 1990s. In 1995 the road to the cave was completed, now it was possible to drive there by car or take a bus. There is a public transport bus from the harbour every hour, and there are busses by tour operators from Antiparos to the cave. Be careful, as far as we know, the fee of the tour operators does not include the entrance fee to the cave. One year later electric light was installed. Now the cave actually was a modern show cave. Still the descent and later ascent of 411 steps is rather strenuous, and it is recommended to take a bottle of water with you.

The cave and its surroundings were renovated in 2009. A new 411-step concrete staircase with a protective railing, which is spacious and safe, was built. Security cameras and a new LED light system were installed. The ticket to the cave includes a free visit to the Historical and Folklore Museum of Antiparos.

The cave was open to the surface for a very long time, the result of a collapse of the cave ceiling. The cave is entered down the slope of a huge collapse doline with a limestone cliff at the far end. There are two small chapels at the entrance, which are named Agios Ioannis Spiliotis (Ai Yiannis) and Zoodohos Pigi. The first is the reason why the cave is also called Cave of Agios Ioánnis. And it is the reason why the cave is extremely frequented on 7th and 8th of May, the eve of and the day of Ai Yiannis. The locals have a celebration with local food and drinks, and the site is crowded.

At the bottom of the doline is a huge entrance portal which is 20 m wide and 10 m high and quite impressive. It is used as an open air church on certain occasions. The cave is actually a single huge chamber which becomes wider and higher, and goes down all the time. Nevertheless, the cave is divided into four sections by the guides, the Antechamber, the Chamber of the Stone Waterfalls, the Chamber of the Cathedral, and finally the Royal Chamber. The Chamber of the Cathedral contains a huge stalagmite, which is said to be 45 million years old, and the most ancient in Europe. The Royal Chamber got its name after the visit by King Otto, the King of Greece, in 1840.

- See also

Historic Show Caves

Historic Show Caves Search DuckDuckGo for "Cave of Antiparos"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Cave of Antiparos" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap Antiparos - Wikipedia (visited: 17-JAN-2026)

Antiparos - Wikipedia (visited: 17-JAN-2026) Antiparos Cave (2021 Opening Hours And Tickets) (visited: 21-MAY-2021)

Antiparos Cave (2021 Opening Hours And Tickets) (visited: 21-MAY-2021) The Caves of Antiparos have a surprise for us! (visited: 21-MAY-2021)

The Caves of Antiparos have a surprise for us! (visited: 21-MAY-2021) Cave of Agios Ioannis-Agia Paraskevi-Antiparos (visited: 21-MAY-2021)

Cave of Agios Ioannis-Agia Paraskevi-Antiparos (visited: 21-MAY-2021)

Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps