Surtshellir-Stefánshellir system

Surtshellir - Stefánshellir - Íshellir

Useful Information

| Location: |

approx. 8 km NE of Kalmanstunga. From Reykjavík take road No. 1, 20 km, after Borgarnes turn right to No. 50, then take No. 580. After you passed the Hraunfossar waterfalls (near Húsafell) and road F35 (Kaldidalur) turn right again at the farm Kalmanstunga. Follow rough track (4WD necessary) up to the lavafield Hallmundahraun and follow the signs Íshellir, Surtshellir, Stefánshellir. (64.7787385, -20.7261495) |

| Classification: |

Lava Tube Lava Tube

ice cave ice cave

|

| Light: | bring torch |

| Dimension: |

Íshellir: L=500 m (approx.), T=0 °C. Surtshellir: L=1,970 m, VR=37 m, T=2-5 °C. Stefánshellir: L=1,520 m, T=2-5 °C. |

| Guided tours: | |

| Photography: | allowed |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: |

Michael Laumanns (1987):

Die Höhlen Islands,

Mitt. Verb. dt. Höhlen- u. Karstforscher, 33 (1), pp 4-15.

E. Waters (2001): Lava Tubes are Boring?, Shepton Mallet Caving Club, Journal Series 10, Number 9, Spring 2001, page(s) 305-312. E. Waters (2001): Caves of the Laki Fires, Shepton Mallet Caving Club, Journal Series 10, Number 10, Autumn 2001, page(s) 337-418. |

| Address: | |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 1679 | first described by Arngrim. |

Description

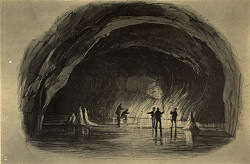

Surtshellir translates to Fire Giants Cave, which gives a first impression of the way, this cave was formed. It is the result of a lava flow about 1000 years ago. It’s actually a single tunnel which is the former flow of basaltic lava, the surface of the lava solidified by cooling forming a tunnel. The tunnel has a more or less constant size, which is up to 15 m wide and 10 m high. However, while the diameter was necessary for the lava to flow through, the form changes and so there are low and wide sections as well as narrow and high ones. The Surtshellir section is about 2 km long and as all three caves

All three caves are parts of the same lava tube, formed by the same lava flow. But at some locations the roof collapsed completely and thus left three pieces, which are not connected any more. In speleology, a cave system is defined as all cave passages which are connected. The three caves do not really fulfill this definition, but the geologic connection is so obvious, that we can talk of a single cave system. However, the addition of all cave lengths for statistical reasons is not correct. There are numerous sources which claim this to be the longest cave in Iceland with a length of a mile, a typical nonsensical superlative. Surtshellir is 1,970 m long, all three together are 3,990 m long There is another cave, the show cave Víðgelmir (1,585 m), which also claims to be the longest. But actually, Laufbalavatn with more than 5 km [2011] is the longest.

Surtshellir was first described by Arngrim in 1679. From this time on, until the end of the 19th century, it was the longest known lava tube of the world. In the early years of scientific cave research, it was also the only known lava tube. This is the reason, why it is the most well known Icelandic cave.

Íshellir is a part of the Surtshellir system with very impressive ice formations. In the winter cold air falls down into the cave, this is a typical cold trap type ice cave. In spring, when the snow on the surface starts to melt, water penetrates into the cave and - as the temperature in the cave is still below 0 °C - freezes to ice stalactites and stalagmites. .

These caves are now a regular tourist attraction. Bring your own lights and wear waterproof clothes and good boots.

Íshellir is the entrance most tourists use. A descent down a boulder slope leads to an extensive ice lake which in 2001 was 30 cm deep in water. Beyond the lake, ice formations abound for some distance, abruptly stopping at an ascent over boulders, where it is necessary to stoop. Beyond the boulders the passage becomes large and muddy. After a large chamber and a couple of short inlet tubes on the right the passage degenerates to a crawl and eventually ends in a complete lava seal.

Up flow from the Íshellir entrance Surtshellir continues in a very impressive style, generally in the form of a 10-15 m diameter tube Much of the passage is liberally scattered with boulders make the going difficult. There are many karst windows, but none are suitable for access without caving ladders. Eventually the cave ends in a collapse which separates Surtshellir from Stefánshellir.

Text by Tony Oldham (2002). With kind permission.

Search DuckDuckGo for "Surtshellir, Stefánshellir, Íshellir"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Surtshellir, Stefánshellir, Íshellir" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark OpenStreetMap

OpenStreetMap Surtshellir - Wikipedia (visited: 15-JAN-2026)

Surtshellir - Wikipedia (visited: 15-JAN-2026) Complete Guide to Iceland’s Surtshellir Lava Cave (visited: 15-JAN-2026)

Complete Guide to Iceland’s Surtshellir Lava Cave (visited: 15-JAN-2026) Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps