Barbarossahöhle

Barbarossa Cave

Useful Information

| Location: |

Mühlen 6, OT Rottleben, 99707 Kyffhäuserland.

A7 exit Seesen (Harz), B243 66 km to Nordhausen, F80 16 km to Berga, F85 to Bad Frankenhausen, after 12 km turn right to Rottleben. Between Steinthalleben and Rottleben, at the Kyffhäuser. 1.5 km NW Rottleben, 5 km NW Bad Frankenhausen. (51.375469, 11.036442) |

| Open: |

APR to OCT daily 10-17. NOV to MAR Tue-Sun 10-15 Closed 24-DEC. [2023] |

| Fee: |

Adults EUR 9.50, Children (3-16) EUR 6, Children (0-2) free, Students EUR 8.50, Disabled EUR 8.50, Familiy (2+3) EUR 27. Groups (15+): Adults EUR 8, Children (3-16) EUR 4. Foto and Video Permit EUR 2. [2023] |

| Classification: |

Karst Cave Karst Cave

gypsum cave,

Zechstein, anhydrite gypsum cave,

Zechstein, anhydrite

|

| Light: |

Electric Light Electric Light

|

| Dimension: |

L=1,100 m, 154 m asl, T=9 °C, H=96 %. Biggest lake: L=50 m, D=3m |

| Guided tours: |

L=800 m, VR=20 m, D=60 min, St=58, Max=80. tour in cave: L=600 m. entrance tunnel: L=168 m, 1898. exit tunnel: L=30 m, 1926. V=100,000/a [1999] V=200,000/a [2000] V=70,000/a [2016].

|

| Photography: | with permit |

| Accessibility: | no |

| Bibliography: |

Anon (no year):

Die Barbarossahöhle im Kyffhäuser,

Hrsg: Einrichtung Erholungswesen, 06567 Rottleben/Kyffhäuser, Tel: +49-3467-4586-2033

Friedrich Herthum (1868): Die Barbarossahöhle bei Frankenhausen am südlichen Rande des Kyffhäuser-Gebirges in ihren interessanten geologischen Erscheinungen beleuchtet Wartig, Leipzig 1868 (16 S.).

Ferdinand Senft (1869): Die Barbarossa-Höhle am Kyffhäuser-Berge Das Ausland (= Ueberschau der neuesten Forschungen auf dem Gebiete der Natur-, Erd- und Völkerkunde) 42, 24: S. 571-573; Augsburg (J. C. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung)

Michael K. Brust (2015): Die Barbarossahöhle im Kyffhäuser. Ein Rückblick auf die 150-jährige Geschichte einer Schauhöhle. ARTE Fakt Verlagsanstalt, Kyffhäuserland 2015, ISBN 978-3-937364-30-8.

Janina Baumbauer (2018): Die Barbarossahöhle in Rottleben im Kyffhäuserland Naturdenkmalführer 1, Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2018, ISBN 9783795471163.

|

| Address: |

Barbarossahöhle im GeoPark Kyffhäuser, Mühlen 6, OT Rottleben, 99707 Kyffhäuserland, Tel: +49-34671-5450.

E-mail: |

| As far as we know this information was accurate when it was published (see years in brackets), but may have changed since then. Please check rates and details directly with the companies in question if you need more recent info. |

|

History

| 31-AUG-1860 | tunnel for copper slate mining built by the entrepreneur Wilhelm von Born from Dortmund. |

| 20-DEC-1865 | after 178 m the cave was reached by the tunnel of the miners Christian Nachtweide, August Schumann and Heinrich Vollrodt. |

| 1866 | development and inauguration under the name Falkenburger Höhle. |

| 19-AUG-1869 | Heinrich Vollrodt had a lethal accident in the cave. |

| 1891 | new owner, renamed into Barbarossahöhle, the desk and chair of Barbarossa erected, and Ballroom prepared. |

| 1895 | electric light. |

| 1898-1899 | new tunnel into the cave built. |

| 1913 | detailed exploration and survey by Dr A. Berg. |

| 1926 | another tunnel into the cave built, used as new exit. |

| 1935 | discovery of additional passages by Stolberg. |

Description

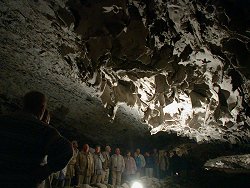

The Barbarossahöhle is entered through a long mine tunnel. The tour shows most of the cave, only a small part is too low for the average visitors. The whole cave is rather voluminous.

The cave has numerous big lakes with gypsum rich water, which shows a unique green colour. This colour is produced by the filtering of white light by the dissolved Gypsum. The green colour is deeper where the water is deeper. The water is extremely clear and contains almost no dust.

The cave is formed inside anhydrite (CaSO4). The layers are 1-2 cm thick, and separated by a thin grey layer of clay minerals. The humidity in the cave transforms the anhydrite into gypsum, a process where the anhydrite absorbs water and increases its volume by about 30%. This causes the layers to bend down and forms huge sheet-like structures. The ceiling resembles puff pastry. In the Gerberei (tannery) these sheets grew until they are hanging down about 1 m. It is said, that they were hanging down more than 2 m when the cave was discovered, but they were destroyed by careless cave visitors. As a result, an artificial lake was created underneath to keep the lobes out of reach. These huge sheets of 2 cm thick gypsum, with grey clay on both sides, hanging down folded like leather gave the room its name.

In the chamber called Wolkenhimmel (Clouded Sky) some steps were built, and a sign with the inscription Barbarossahöhle. Here, a photographer takes pictures of the tour group, which you can buy at the exit after the tour. A rather strange sight are the desk and chair of Emperor Barbarossa. They were built at the end of the 19th century, when the legend of emperor Barbarossa was very popular. Only a few steps to the discovery tunnel. At the end of the tour the cave is left through a third tunnel. This one is very short, as the cave is rather close to the surface at this end.

Directly under the anhydrite layer is a thin Kupferschiefer (copper shale) layer, which is easy to reach due to the soft anhydrite. In addition, caves, locally called Schlotten, were often cut to receive the overburden, which greatly simplified mining. Thus, copper shale was mined in the entire area, but especially in the Mansfeld area, for 900 years. While it was profitable at Mansfeld, it never seems to have been here at the Kyffhäuser. The copper content in copper shale varies from region to region, and here it was simply not high enough to be profitable.

On 31-AUG-1860, the entrepreneur Wilhelm von Born from Dortmund started a tunnel. He was the financial backer, and the work was supervised by mine inspector Carl Klett from Frankenhausen and shift foreman Friedrich Leonhardt from Udersleben. The test gallery was driven by three miners from Steinthaleben, Christian Nachtweide, August Schumann and Heinrich Vollrodt, under the steward Heinrich Rödiger from Könitz near Saalfeld. This worked better than which in hard gneiss or granite, but it still took them five years to reach 178 metres. On 20-DEC-1865, they reached the large chimney, and mine inspector Carl Klett and shift foreman Friedrich Leonhardt reported the find to the High Princely Mining Office in Könitz two days later. The princely Schwarzburg mining councillor Friedrich Herthum and his superior, mining master Carl Franck, then showed foresight. They obtained official protection for the cave in order to preserve it permanently for posterity "because of its rare uniqueness and beauty". And so the cave was not destroyed, but transformed into a show cave in a very short time. As early as 1866, it was opened as a show cave under the name Falkenburg Cave, named after the nearby ruin. However, it was also called Rottleben Cave. It was not the first show cave in Germany, Sontheim Cave and Baumann Cave were much earlier, but it was the world’s first show cave in the gypsum karst.

Because of its location in the Kyffhäuser, it was associated with the legend of Emperor Barbarossa from the very beginning. Bergrat Friedrich Herthum used the name Barbarossahöhle (Barbarossa Cave) on the mine plan he drew as early as 1866, the year the show cave was opened. In 1868, he used the name in the first publication that was published about the cave. In other words, the cave was actually called Barbarossahöhle from the very beginning. With the rise of German nationalism at the end of the 19th century, which also led to the construction of the Barbarossa Monument at the Kyffhäuser, this legend became a very profitable advertisement for the cave. The claim that the cave was only renamed in connection with the construction of the monument, which can be read in many places, is obviously false.

The Barbarossa Cave is often referred to as an anhydrite cave, a technical term for karst caves in anhydrite. In fact, anhydrite is the same as gypsum; anhydrite, as the name suggests, simply contains no water, unlike gypsum. But it is obviously a karst cave, and these are based on the dissolution of rock by water, so the anhydrite inevitably comes into contact with water and therefore transforms into gypsum. The term anhydrite cave was introduced into literature by Ferdinand Senft in 1869, using the Barbarossa Cave as an example. He used it to try to distinguish between two types of gypsum caves, assuming that anhydrite caves were formed by the dissolution of rock salt. The reason was that salt dissolves even faster than gypsum and thus there is simply not enough time to convert the anhydrite into gypsum. This theory has since been disproved, yet Barbarossa Cave is indeed a cave in anhydrite, and the lobes in the tannery are formed by the slow transformation of the anhydrite into gypsum, by the humidity of the cave air. Thus, the term anhydrite cave is still used in literature and Barbarossa Cave is type locale (locus typicus).

During the times of the DDR (German Democratic Republic, GDR) this cave was a very popular sight, owned by the state (Volkseigentum or peoples property). The guides were on the payroll of the state, as virtually everybody. Entrance fees were defined by the state and were pretty funny, as they charged strange amounts like 1.45 Marks. They also charged small fees for parking and photography in the cave. After the Währungsunion, when the GDR used the West German Mark, the fees increased slowly to western standards. But still the need to be economic was very problematic for the eastern show caves. West German caves were typically maintained by so-called Vereine, caving clubs were the members worked on an honorary basis. The fees were not enough to pay professional cave guides, at least not during winter when visitor numbers dropped.

Later the so called Fotografiererlaubnis (photography permit) was abandoned, now photography is strictly forbidden. And the explanation of this fact is pretty weird: The guide tells the visitors, that they are not responsible for the proscription. The cave was found during mining activities and so the mining authority was now responsible for the security of the cave visitors. One of their rules is the safety of the paths, which is disrupted by flashlight. Flashlight blinds the other visitors and the eye needs up to 15 minutes to recover completely.

On this explanation, employees at the mining authority, doctors and photographers are confused alike. There is some truth is all this statements, but they are twisted to a weird and wrong construct. And they are pushed to the point of absurdity by the guide, when he askes the visitors to pose for a group picture. Asked about this inconsistence he tells something about special flashlights.

By the way: the pictures on this page were made some years ago with a valid Fotoerlaubnis.

Emperor Barbarossa

Emperor Barbarossa Search DuckDuckGo for "Barbarossahöhle"

Search DuckDuckGo for "Barbarossahöhle" Google Earth Placemark

Google Earth Placemark Barbarossa Cave - Wikipedia (visited: 02-JUN-2023)

Barbarossa Cave - Wikipedia (visited: 02-JUN-2023) Barbarossahöhle, official website (visited: 02-JUN-2023)

Barbarossahöhle, official website (visited: 02-JUN-2023) Index

Index Topics

Topics Hierarchical

Hierarchical Countries

Countries Maps

Maps